In sections 3 and 4 of the introduction to Seeing the Form, Balthasar takes on what he sees as the Protestant evisceration of theological aesthetics. He begins with Luther, moves through Schleiermacher, and ends up at Barth. There’s one author he says who bucks this trend, Gerhard Nebel, who in a way is writing in reaction to Kierkegaard.

There are two themes that stick out for me from these two sections. The first is how much he identifies Protestantism with the dialectic of Luther’s imagination of the Deus absconditus — the God who is hidden — and claims that Protestant theologians constantly engage in extracting out from the supernatural context of the divine beauty that suffuses all creation. I found this framework helpful, because there’s a way where Balthasar is lobbing a more conventional critique of Protestantism here that one also finds in Speyr — and to some extent, in Ratzinger of blessed memory.

The Catholic critique of Protestantism is that schism becomes a habit; once you split, you keep splitting. I’m an Eastern Catholic convert from Protestantism, so you might expect me to share this line of criticism, but honestly, I find it lazy, not least because it doesn’t really speak to my experience. I am intrigued, as a result, by how Balthasar puts it, that when you extract the dialectic of the hidden God from the context of beauty, then it’s like you have to keep on searching for new context, to the point where you forget the point of first extraction. It’s like (forgive me) Maui extracting the heart of Te Fiti in Disney’s Moana, a deeply problematic movie, I know, because that is exactly how Maui would not be in Pacific Islander mythology. But that is also the point. Moana is not a Pacific Islander movie, if Balthasar were to have his way. It’s Protestant animation.

The second thing that emerges from the section on Nebel is beauty as daimonic. While sifting through Nebel’s careful differentiation between the daimonic and the demonic, Balthasar makes a prescient claim that for Protestant theologians, the two often get mixed up, such that theological aesthetics itself becomes spoken of as the work of the devil. Nebel doesn’t fall into that trap, though for Balthasar, he also doesn’t get far enough out of his Protestant framework to have his reality suffused by beauty.

I was reading this at home after a long day at the office. In fact, reading it after coming home made me think about whether I should actually switch my reading habits and do Balthasar and this blog as a warm-up in the morning. I really need to get back to Star Trek for self-care. As followers of my social media will know, my Penguin and I watch The Next Generation every night. We are on the fourth season, so we know what the Borg is now.

But my work at the office yesterday involved less writing and more administrative work. My friends and I are putting together what we are calling a ‘Sinophone’ playlist — it will be ready for public display, eventually — and there was a song that came up as I was working on filling out a form that was asking me to do some retrospective reflection on my professional activities in the last year. It was René Liu’s 後來 (houlai), roughly translatable as ‘At Last,’ with apologies to Etta James.

If Etta’s version is the long sigh of relief at being able to rest in the warmth of love, René Liu spends her time almost turning her voice into a rasp as she curses her fate at finally learning what love is after the dissolution of the world she had with her lover. Certainly, I told my friends (and then later Instagram), it was not because I shared her regrets. My wife later helped me at dinner to articulate it. We like breakup songs, we agreed, not because we have experienced breakups ourselves or because it resonates with our current relationship (it really does not), but because there’s just something about the heartbreak that makes the emotions of the song feel rawer and deeper than happy music.

後來 put me into a really reflective mood, and I put it on repeat so that I could get through the administrative work of the afternoon. I found myself reflecting with friends, then, through the evening and into this morning that this is really what Sinophone music does. It doesn’t matter whether it’s Cantonese or Mandarin or even Hokkien — it’s all the same people, anyway — but the recurring theme is that love is always about the goodness you share with another, so when it all comes crashing down and you lose it, the introspection tells you that it was you who were not good enough for what you had.

The scholar who has really helped me understand this dynamic is probably, in my view, one of the most interesting Sinophone feminist scholars working right now, my friend Ting Guo. Guo is at work on a book that expands on what I consider her instant classic of an article, ‘Politics of Love,’ where she demonstrates that the consistent affect in Chinese governance from Qing China through the various nationalisms and communisms of the modern nation-state is that of love. Guo’s analysis hews close to government structures, but I think a case can be made for an extension of her reading to how Sinophone communities work too. After all, as she once tweeted, I did learn the word ‘Sinophone’ from her, after, I said, checking my ‘toxic masculinity.’ ‘Be like Justin,’ she exhorts her reader.

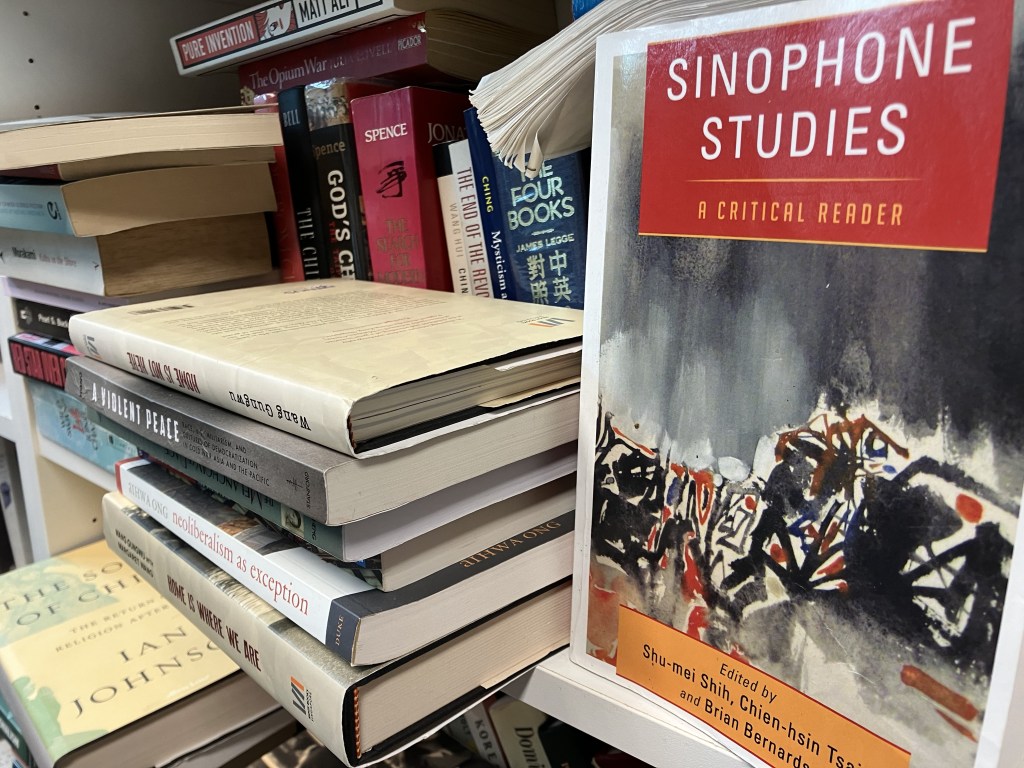

The way that 後來 descended on me, I’ve been reflecting, is more or less like the daimonic beauty that Balthasar describes. What’s funny is that the ‘Sinophone,’ with its claims to constant fragmentation and differentiation among various communities that speak ‘Sinitic’ languages (as its coiner Shu-mei Shih puts it), sounds a lot like the fragmentation that Balthasar is attributing to Protestantism too. But just like the lazy critiques of Protestants constantly splitting (to the point where I know some Latins offensively write off the Orthodox as Protestants too, because of the differentiation that we make among local churches and their catholicity), the concept of the Sinophone is not Protestant, and I say this as someone who has submitted a book manuscript to the University of Notre Dame Press arguing that the Cantonese-speaking Protestants I talked to in Pacific Rim societies, who are themselves a Sinophone people, referred to themselves as ‘a sheet of scattered sand.’

Balthasar’s insight here, in other words, is not just about Protestants. It’s about modernity and the way that daimonic beauty is often detached and uprooted from aesthetic contexts and put into new ones. It is, as one of the speakers in Mok Zining’s Orchid Folios puts it, because ‘a word is a cutting, / a sentence, a bouquet,’ which means that you can ‘scatter / cuttings in / a tub of water,’ which are the ‘new context / into which / they have been / plunged’ (‘Floristry Basics: Cuttings,’ p. 19). If the decontextualization of the hidden God is a Protestant phenomenon, then this Protestantism must be placed into the narrative of modern secularization that has done the same for so much of what Balthasar calls theological aesthetics.

And yet, like Nebel, there are glimpses of its remnants. One place, I’m saying, is in Sinophone music like Liu’s 後來, which descended on my cold administrative afternoon with the warmth of its regretful and wise love. Not having heard much Liu because my cantopop is much stronger than my mando, I went to see what all the fuss about her was about. Her nickname, apparently, is Milk Tea.

Immediately, I was at home. You know a Sinophone person when they call it Milk Tea, 奶茶, that refreshing goodness that is warm in its coolness, filling in its almost seeming emptiness. Isn’t it the same with Balthasar’s reading of Nebel, I reflected? This Protestant is longing for the daimonic in its aesthetic context, just like we Sinophone folk seek love in the home we always seem to lose, until we come to find it in another person, in a body, in a physical figure that is irreducible to ideology, philosophy, or ideation.

Sinophone music, I reflected, is where I can see a glimpse of The Glory of the Lord. 後來.

Leave a comment