As the introduction to The Glory of the Lord winds to a close, Balthasar’s sweeping vision for revising how theology might be done through the ontological intervention of theological aesthetics comes together. Helpfully, he writes of its two dimensions toward the end:

- The theory of vision (or fundamental theology): ‘aesthetics’ in the Kantian sense as a theory about the perception of the form of God’s self-revelation.

- The theory of rapture (or dogmatic theology): ‘aesthetics’ as a theory about the incarnation of God’s glory and the consequent elevation of man to participation in that glory. (Seeing the Form, 125).

It comes at the end of what I can only describe as a lytia of names as he begins to describe what he means by a ‘Catholic’ theological aesthetics, reaching all the way back to the Logos in Paul and Justin and coming together in the Areopagite. There are pages and pages of him almost playing Schweitzer as he sinks into the Romantic theological worlds of Hamann, Herder, Gügler, noting that their fusion of heaven and earth, revelation and creation, was no match for the cold neo-Thomist eviscerations that came in their wake. And yet, there is Scheeben, who still pursues in the time of the theological wasteland a search for the link between theological beauty and the beauty of the world, as he puts it repeatedly.

There is a point, I reflect, in Balthasar naming all these men. He is not name-dropping; he is saying that each of these guys — and above all, he notes, the apophatic guys like the Areopagite and John of the Cross, who never forgot the created order as they pursued the path of negation to the divine — opens up vistas into theological aesthetics, that God is the ground of the beauty of the world because the form is irreducible to abstractness. And yet, that is also the point. In this path from early Christianity to the Romantics and their discontents, the players, it seems, are men, which is something that Balthasar also notes in First Glance at Adrienne von Speyr. For some reason — and even though Speyr is his spiritual friend — this ‘feminine’ approach to grace, as he puts it at one point, is embodied in the gaze of men.

I reflect on this as I think about the various people I’ve been bringing into dialogue with this theological aesthetics: Diana Fu, Mok Zining, Ting Guo, Shu-mei Shih, René Liu, even Taylor Swift. With the exception of one (Swift), these have all been Sinophone women writers, none of them Catholic. Some of them are my friends, and I think that is close to what I am thinking about as I consider Balthasar’s sweeping theological vision. It is the relationship between friendship and communion.

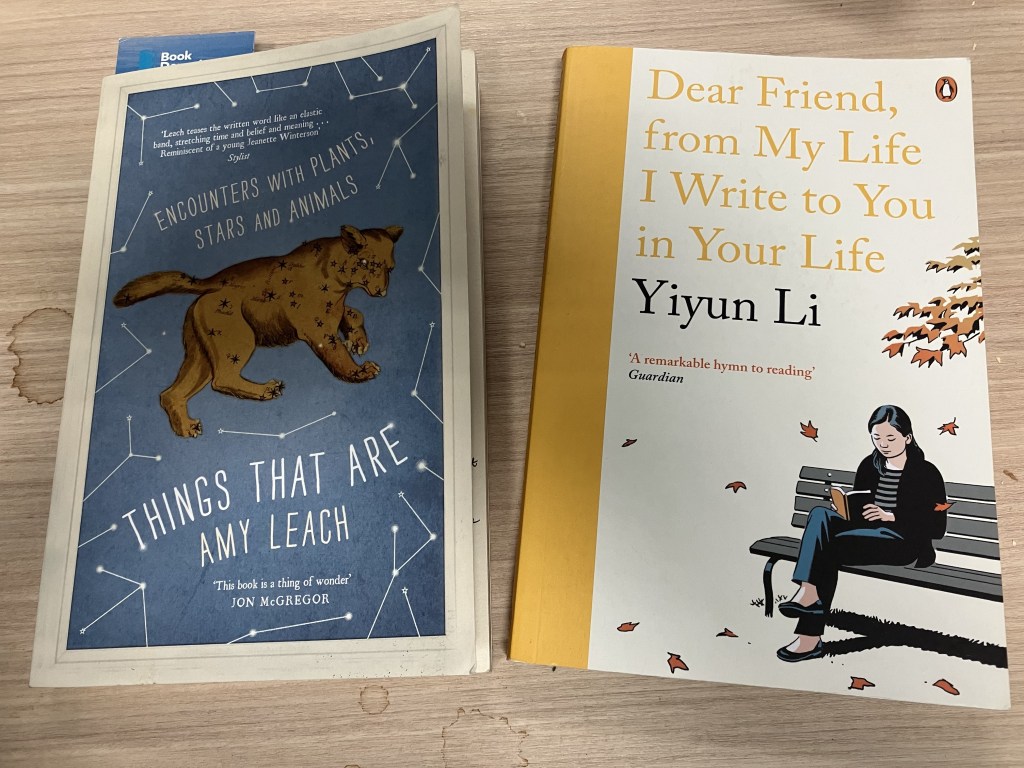

I had sudden inspiration this morning to try reading Amy Leach’s book Things That Are: Encounters with Plants, Stars, and Animals again. I’ve been trying on and off, mostly because Zining put it on my desk last year, but also because Leach is very good friends with the author of another piece Zining put me onto a few years ago, ‘To Speak Is to Blunder,‘ by Yiyun Li. This essay is actually part of a collection titled Dear Friend, From My Life I Write to You in Your Life, which in halting and whispering prose considers Li’s relationship with suicide, her decision to write solely in English instead of Chinese when she moved to America, and her literary friends, whom she finds in books, in letters, and in person.

Part of why I’m able to enter back into Leach’s Things That Are is probably because today, my church celebrates the Feast of Theophany, in which Christ is baptized by John in the Jordan. But if I’ve learned anything in the past seven years as an Eastern Catholic convert, the significance of feast days can also be overrated. The greater truth is that I’ve simply needed time to mull over Leach, with her odes to an open Tomorrow, the mislabeling of beavers as fish by a Bishop of Rome, and the what-ifs of the organ sounds of Odo of Cluny surviving into the present instead of dissipating into the ether, as sound waves do.

I’m not done with Leach yet, but as I read Balthasar, I thought about Li and Leach’s friendships, as well as my own. When you have friends, you begin to see the world in what Balthasar more or less terms an ‘ecstatic’ way. You come out of yourself, you enter into new worlds, and they enter into you. Suddenly, new possibilities open, and the future becomes unpredictable: ‘even after thousands of years,’ Leach opens, ‘we have had no luck conquering Tomorrow’ (Things That Are, xi).

And so, when Leach invites the reader to consider with her the trees, the beavers, the fish, the geese, and so on, of course she invokes the Trappist monk who says, ‘I am a Trappist like the trees,’ even as ‘the lily, the creek, and the fishes and the rain’ call themselves Trappists (Things That Are, 3). This is more than a Franciscan vision; it is much closer to Balthasar’s monastic vision in the Areopagite and John of the Cross, that the way of negation and renunciation actually binds a person to the possibility of theological aesthetics and from there opens one’s being to the beauty of the world.

The way here, for Balthasar, is of course divine ecstasy, the form of Jesus Christ. But in God becoming man for man to become God, as the Athanasian formulation would have it, there is a fresh insight, that such divine friendship divinizes all my friendships, that such ecstasies are possible because the ecclesia does not bind the beauty of the world but that the sæculum itself is not as godforsaken as one might think it to be, and that it has often been theology itself that has been the culprit in the modern stripping of the beautiful. Balthasar and Speyr may have found a home in the Latin Church as I have found mine in the Kyivan, but it is simply the table at which we commune as a foretaste of the redemption of the entire oikonomia.

And so, in the meanwhile, my friends write to my life from their own lives, and I do the same for them. But in reading what they write and entering into the worlds that they show me — just like Balthasar does with Hamann, Herder, and Gügler — I enter not simply into their subjective reality, but in what Amy Leach calls the things that are, that which is alive in the world and encounters me in my life too.

Leave a comment