I don’t feel like I read Balthasar very well today and may have to return to dwell on his words. For me, the term pistis and gnosis are familiar ones from my childhood, words I knew to denote faith and knowledge in the New Testament. I let these words wash over me, sometimes wondering whether I was reading about what I thought the words meant or what Balthasar was meaning by them.

What I did pick up is that faith is a sense, and perhaps a sensibility. It is through the sense of faith that one beholds divine light, he is saying, and that light is not abstract. It is the radiance of the physical form of Jesus Christ, the one who reveals to humanity what God looks like.

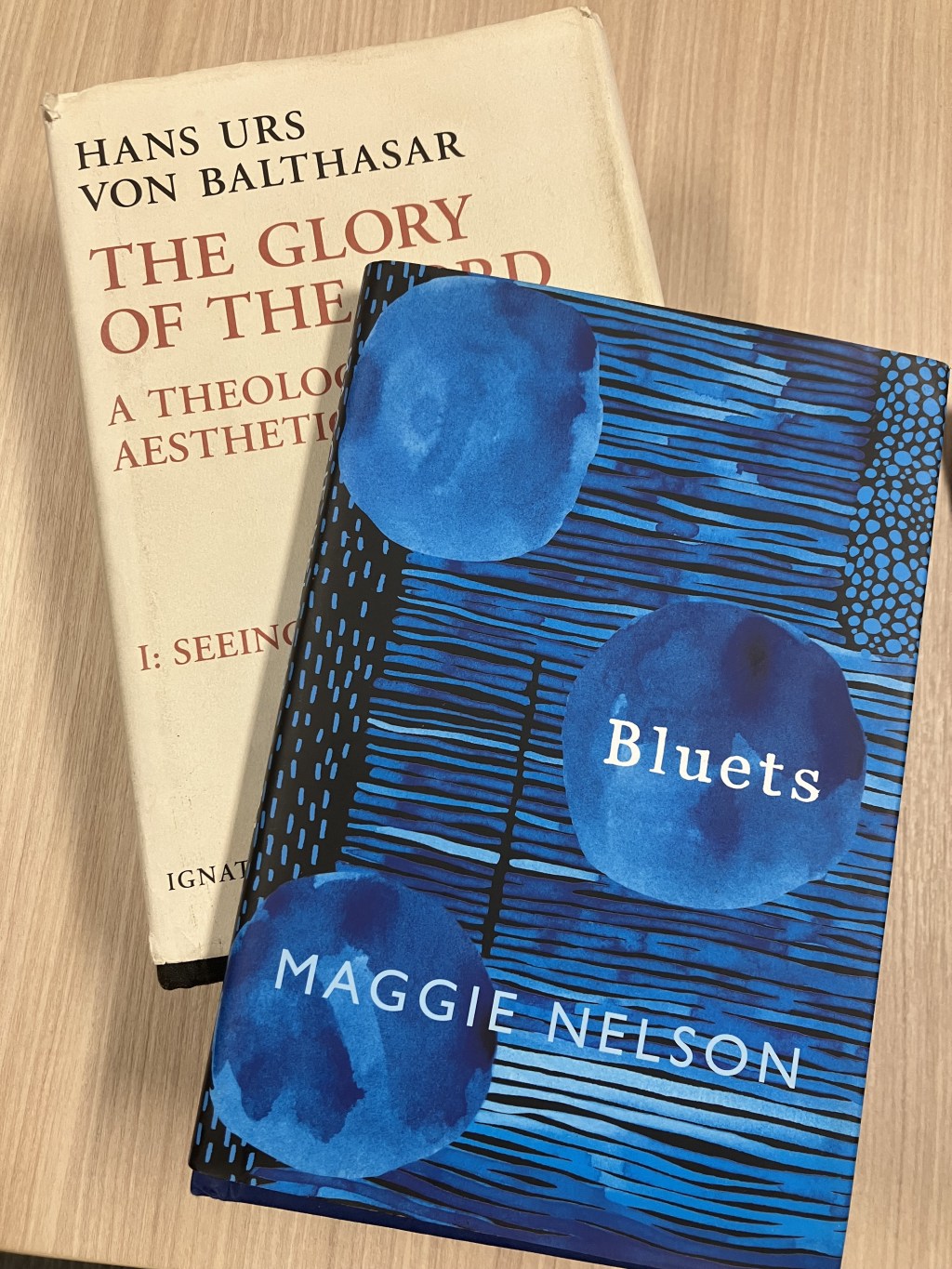

And yet — and this is what brought me right to the docupoet Maggie Nelson’s modern theological classic Bluets — Balthasar is not willing to stop there. Yes, indeed, the ‘finitude’ of Jesus allows us to behold the divine infinite. ‘But the resurrection of the flesh vindicates the poets in a definitive sense,’ he continues, ‘the aesthetic scheme of things, which allows us to possess the infinite within the finitude of form (however it is seen, understood or grasped spiritually) is right’ (Seeing the Form, 155).

Maggie Nelson is to me such a poet. Bluets is a classic of docupoetry, I am told, blending creative nonfiction, nontraditional poetics, and perhaps a little fiction if you spot it, and not just a little bit of theology. Certainly, there is music too — Joni Mitchell’s Blue is prominent, as is Billie Holiday and Leonard Cohen. The sections on Dionysius the Areopagite are just divine — not that she is religious, she wants to emphasize. ‘Whenever I speak of faith,’ she says

I am not speaking of faith in God. Likewise, when I speak of doubt, I am not talking about doubting God’s existence, or the truth of any gospel. Such terms have never meant very much to me. To contemplate them reminds me of playing Pin the Tail on the Donkey: you get spun around until you wander off, disoriented and blindfolded, walking gingerly with a hand stretched out in front of you, until you either run into a wall (laughter), or a friend gently pushes you back toward the game (Bluets, 48).

But isn’t this exactly what Balthasar is talking about? The sensorial quality of faith has to have something it is reaching for, a desire, a direction. ‘Suppose I were to begin by saying I had fallen in love with a color,’ she opens (Bluets, 1). That colour, she reveals fairly quickly, is the colour blue, which is why the book is called Bluets. She is asking us to contemplate, just like Mok Zining later does in The Orchid Folios (a text clearly inspired by Bluets), the flowers of the field, the colour it evokes, and its constellation in what we might call ‘blue,’ though what that is in essence, who can know?

Is this not what Balthasar also means in a passage that, like many in Bluets, at once roused me and disturbed me:

A thorough-going analysis of faith is, therefore, a contradiction in terms, since it would annul precisely the act which it seeks to posit. Faith-analysis is just as impossible as psychoanalysis — so long, that is, as by psyche we mean that depth of man and his destiny where man stands before God himself and where he can understand and explain himself only in light of the Word which God speaks to him. (Seeing the Form, 142-143).

Both the subjective act of faith and the subject of faith are, Balthasar is trying to say, integral mysteries that cannot simply be taken apart and sorted. It can only be approached by desire, though whether it can be fully known is another story — and whether or not that was in fact the Freudian project in the end is also, in my view, an open question. Nelson, unafraid of her Freud, is much more direct than Balthasar: ‘There is color inside of the fucking,’ she writes imaginatively of someone who might be good at the act, and alas someone who also is quite possibly also bad in other acts, ‘but it is not blue’ (Bluets, 19). The skill dissolves. It gets lost in the form of the body.

Who is Maggie Nelson writing for? Who is reading Balthasar? These are the questions he considers as he turns to the relation of I and You in the light of faith. ‘The mystery of I-Thou within the Godhead,’ he writes, ‘must find its epiphany in an I-Thou mystery between God and man; in this way, myth is both fulfilled and surpassed. (Seeing the Form, 147). Blue tells us everything about existence. But there is also more than blue in the world, when I have you, and the you may start for Balthasar in Christ, but that you also becomes the world where bluets grow and Bluets is sung from the very intimacy of bodies that are irreducible to anything but the physical, animated by light.

Leave a comment