As Balthasar opens, the problem announces itself. It is, as Edward Said also noted later on, the problem of the beginning. The first word a theologian starts with is ‘the truth of the growing kingdom of God both as it now is in the fulness of God’s creation and also in the weakness of the grain that dies in me and in all my brothers, in the night of our present and in the uncertainty of our future’ (Seeing the Form, 17). Where theology begins, Balthasar is saying, cannot be so narrow as to rule out the pain and existential dread of modernity. It must begin capaciously.

And so he begins, famously, with ‘a word with which the philosophical person does not begin, but rather concludes’ (Seeing the Form, 17). Here are the famous passages, namely:

Beauty is the word that shall be our first. Beauty is the last thing which the thinking intellect dares to approach, since only it dances as an uncontained splendour around the double constellation of the true and the good and their inseparable relation to one another. Beauty is the disinterested one, without which the ancient world refused to understand itself, a word which both imperceptibly and yet unmistakably has bid farewell to our new world, a world of interests, leaving it to its own avarice and sadness. No longer loved or fostered by religion, beauty is lifted from its face as a mask, and its absence exposes features on that face which threaten to become incomprehensible to man. We no longer dare to believe in beauty and we make of it a mere appearance in order the more easily to dispose of it. (Seeing the Form, 18).

Beauty, in other words, has been discarded in modernity, subjectivized, dissected, analyzed, anything but taken as a whole in wonder. Beauty, Balthasar continues, requires that a person see the form — the physical without psychologizing it, a body without reducing it to a soul, a text that presents itself as a seamless image instead of its exegetical parts, a marriage that is ‘the form that chooses’ the spouses ‘because they have chosen it, the form to which they have committed themselves in their act as persons’ with their full bodies (Seeing the Form, 27). You don’t take apart beauty, Balthasar says. Beauty takes you into its form.

‘Begin again,’ one of the speakers says in the Singapore writer Mok Zining‘s Singapore Literature Prize-shortlisted début The Orchid Folios. It would be no exaggeration to say that Mok’s work is what brings me back to Balthasar and Speyr time and time again, though she, like Diana Fu, is in no way Catholic, not even close. Mok’s piece, ‘Arabesque: A Series of Revelations’ constantly reminds me of these passages on beauty, though it is not my focus today.

What I want to say is that writers like Fu and Mok, both in full disclosure dear friends and former students of mine, are secular transpacific writers, both of whose work raises questions about Balthasar’s strident declaration that not only is ‘to be a Christian…precisely a form,’ but that it is also the most ‘holistic, indissoluble, and at the same time more clearly contoured’ kind (Seeing the Form, 28) — unless he means the same thing as Gil Anidjar in Blood: A Critique of Christianity, where everything everywhere all at once, so to speak, is flowing with the secularized blood of Christ. His directee Adrienne von Speyr’s own husbands were, after all, not always themselves very practicing as Christian, as I understand from First Glance at Adrienne von Speyr. The beauty of the form is not limited to a Christian apologetic, if my encounters with transpacific writing and Sinophone friendship are anything to go by. It is the longing of godforsaken modern secularity, even in this region that encircles and traverses an ocean whose floating garbage patch and potential to erode many a coastline of residential settlement is the source of so much contemporary climate anxiety.

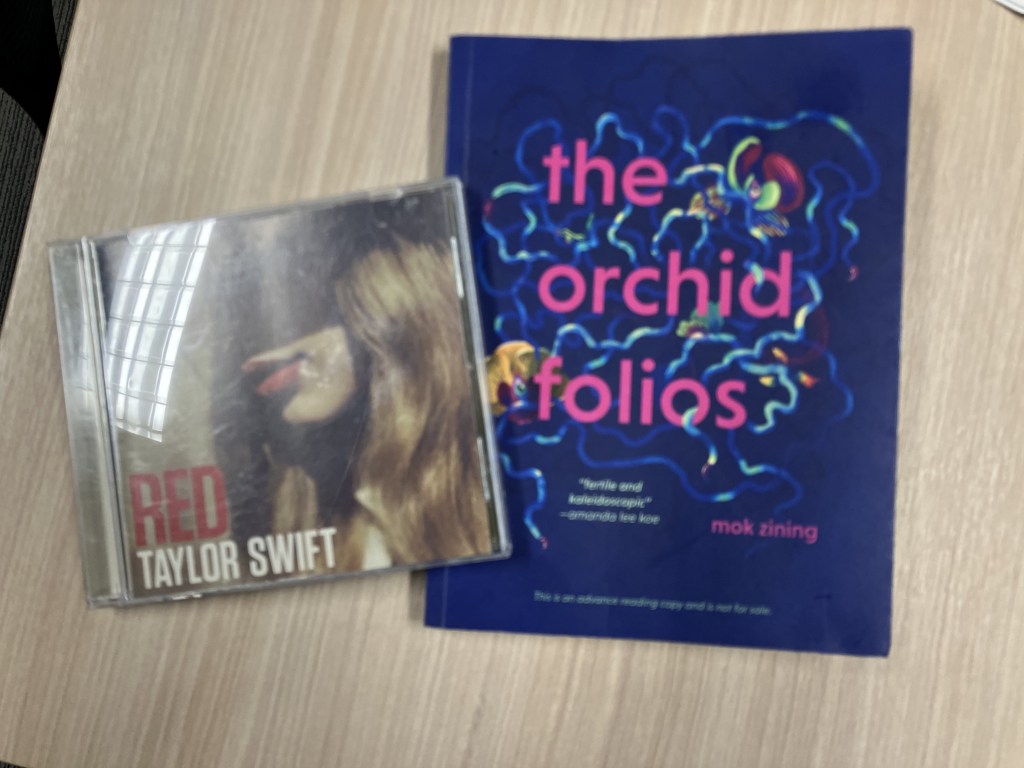

What is Mok saying, with her invocation, ‘Begin again’? This comes toward the end of her book, which in one of the plots discusses the history of the orchid Vanda Miss Joaquim as the national flower of Singapore and its place in the circuits of British Empire. The story goes that the Armenian woman who bred the national breed, Agnes Joaquim, was systematically written out of the story by colonial men and their postcolonial heirs who thought that women have no place in the story. ‘Begin again,’ she says, almost like Taylor Swift after the furious emotions of Red. More than a century after Agnes Joaquim’s death, a scholarly campaign reinstates her in her place as an agent in history. The wholeness brings a glimpse of healing. The form of the orchid becomes whole, not just, to use one of Mok’s favourite refrains, a set of cuttings.

They who pick beauty apart are the real fools and philistines, Balthasar is saying, and here Mok concurs. Begin again, they are both saying, and what you will find, despite the significant ideological difference between Balthasar and Speyr’s rigidly idealistic gender roles born of German idealism and Mok’s Sinophone feminist meditations, is that beauty is Woman, and her name is Sophia, the Lady in prophetic and wisdom literature. Forsake her, and with Fu, it could be said that real godforsaken rains had not fallen in years. It’s not just that you won’t have wisdom. It’s that you’ll have a wasteland.

But find her again, and though I am sure that Fu and Mok would both judge me, a straight Asian American man who cannot help but to love Taylor (and not only Charles — but Swift especially), for saying this, I must end with Swiftie words: but on a Wednesday, in a cafe, I watched it begin again.

Leave a reply to jkhtse Cancel reply